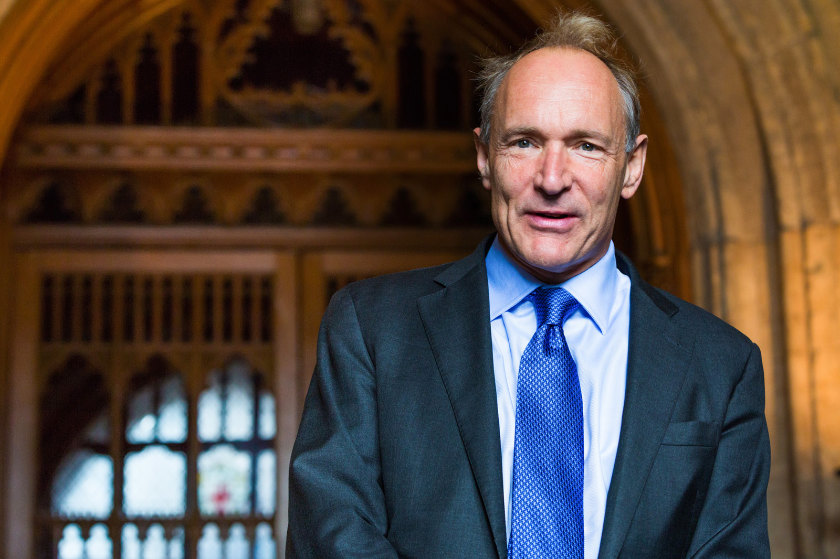

Paul Clarke/CC BY-SA 4.0, commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37435469

Above: Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web.

Earlier this month, Sir Tim Berners-Lee wrote an open letter expressing his concerns about the evolution of his invention, the World Wide Web. (Interestingly, he writes the term all in lowercase.)

It wasn’t just about ‘fake news’, which is how the media have reported it. His first concern was, in fact, about our losing control over our personal data, and determining when and with whom we share them. It’s something I’ve touched on regularly since 2011, when Google breached its own stated policies over user-preference collection for advertising purposes, something that Facebook appears to be following suit with mid-decade. This was long before Edward Snowden blew the lid on his government’s monitoring, something that’s happening to citizens of other occidental nations, too.

Sir Tim writes, ‘Through collaboration with—or coercion of—companies, governments are also increasingly watching our every move online, and passing extreme laws that trample on our rights to privacy. In repressive regimes, it’s easy to see the harm that can be caused—bloggers can be arrested or killed, and political opponents can be monitored. But even in countries where we believe governments have citizens’ best interests at heart, watching everyone, all the time is simply going too far. It creates a chilling effect on free speech and stops the web from being used as a space to explore important topics, like sensitive health issues, sexuality or religion.’

But the one that struck me as very pertinent to publishing is Sir Tim’s second point. It’s the one that most news outlets seized on, linking it back to ‘fake news’, a term now corrupted by the executive branch of the US Government when attacking coverage that it doesn’t like. However, Sir Tim’s points were far broader than that. And it’s evident how his first point links to his second.

It’s not hard to see that there is biased coverage on both the right and right wings of US politics (interestingly, they call it left and right), although Sir Tim points to how ‘a handful of social media sites or search engines’ show us the things that appeal to our own biases through their algorithms. ‘Fake news’ then spreads through these algorithms because they play to our prejudices. He writes, ‘those with bad intentions can game the system to spread misinformation for financial or political gain.’ These sites are able to determine what we see based on the data we’ve given them, willingly or unwillingly.

It’s so far from the ideals of the World Wide Web that it’s sad that the medium, which was once so expansive and inspirational as we surfed from one site to the next to read and absorb information, has come to this: a tool for becoming more insular, the first path to the idiocracy.

Google, as I wrote last year, biases itself toward larger sites, no longer rewarding the media outlet that breaks a news item. The incentive to be that maverick medium is, therefore, lessened greatly online, because the web isn’t being ranked on merit by the largest player in the search-engine business. It’s why Duck Duck Go, which doesn’t collect user data, gives search results that are generally fairer. We think it’s important to learn alternative viewpoints, especially in politics, otherwise the division that we already see in some countries will only deepen—and at worst this can lead to war. In peacetime countries, a compatriot with opposing political thoughts is not our enemy.

Facebook’s continued data collection of user preferences is also dangerous. Even after users opt out, Facebook’s ad preferences’ page demonstrates that it will keep collecting. Whether or not Facebook then uses these preferences is unknown—certainly Facebook itself clams up—but since the site reports journalists who alert them to kiddie porn, kicks off drag queens after saying they wouldn’t, and forces people to download software in the guise of malware detection, who knows if any of Facebook’s positions are real or merely ‘fake news’? Knowing the misdeeds of sites like Facebook—and Google which itself has been found guilty of hacking—do they actually deserve our ongoing support?

Of course I have an interest in getting people to look beyond the same-again players, because I run one media outlet that isn’t among them. But we have an interest to seek information from the independents, and to support a fair and neutral internet. We may learn an angle we hadn’t explored before, or we may find news and features others aren’t covering. Better yet, we may learn alternative viewpoints that break us out of our prejudices. Surely we can’t be that scared of learning about alternatives (maybe one that is better than what we believe), or having a reasoned debate based on fact rather than emotion or hatred? And if you are sharing on social media, do you want to be one of the sheep who uses the same click-bait as everyone else, or show that you’re someone who’s capable of independent thought?

It shouldn’t be that difficult to distinguish fake-news sites from legitimate media (even though the line gets blurred) by looking at how well something is subedited and how many spelling mistakes there are. Perhaps the headlines are less emotive. There is a tier of independent media that deserves your support, whether it is this site or many competing ones that we’ve linked ourselves. Going beyond the same-again sources can only benefit us all.—Jack Yan, Publisher

Leave a Reply